"VITAMIN FOR THE SOUL" by Emad El-Din Aysha

“And still, after all this time,

The sun never says to the earth,

‘You owe Me’.

Look what happens with

A love like that,

It lights the Whole Sky.”

“Look at that. What does it remind you of?”

Dr. Kanji Li had just put an orange effervescent tablet into a half-filled glass of water.

His esteemed colleague Dr. Yingluo Mika shrugged her shoulders. Her hair was like dark cords draped on the white expanse of her lab coat, as spotlessly clean as his own. The skirt she wore beneath the coat was black, just as were his trousers

“The sun dissolving into the sky,” he said triumphantly.

“Isn’t that what we’re going to do here, Kanji-san? Drown away the sand. Turn it from the red planet to the blue planet to, eventually, the green planet.”

“Please, Kanji is enough. It will go from the planet of war to the planet of peace. A second Earth, with yourmagical touch.” He groped for her fingers. She pulled away respectfully but stood her ground.

They glanced off the white metal scaffolding holding them up in the space station, down on to the dark side of the planet, with its little clots of light and humanity, scattered across the Martian landscape.

“Then we can finally settle down, set roots, and feel some real gravity for a change,” he said.

“I’d be a grandmother by then.”

“You willbe a grandmother, just not up here,” Kanji insisted.

“Yes, but who will be my suitor?”

He sighed in silence but smiled inwardly nonetheless.

***

“The skies belong to the Japanese, the lands to China. This is as fair a bargain as is possible,” the gray-uniformed ministry official told his youthful assistant.

“But why not both for us, sir?” His assistant was dressed in green work clothes, reminiscent of a military uniform, with a slight grayish hue.

“Because we have enough troubles of our own down here,” he said, looking out at the factory floor from his metal-plastic office. The Uighur workers were busily churning out respirator units for the exploration parties mapping the planet and testing the soil.

“Would not our own labor work better? We would not need an interpreter, at least.”

“That is the whole reason why we are here, so we do not have to use interpreters back home.”

“But respectfully, what has the Uighur to do with Mars?”

“What has the Uighur have to do with Syria? The last Great War the world fought, that we fought, was with the likes of these, mobilized from camps round the four corners of the Earth. We cannot afford another. None of us.”

“But we won the war, sir.”

The ministerial official dragged his gaze away from the shop floor to look out the window of the factory dome, where they worked and slept, to the hostile terrain beyond. “Won by the skin of our teeth. We have become too accustomed to green hills and city gardens. We are in a desert, and no one tames a desert like a nomad.” He turned to look at his assistant, as if to scold him. “And never underestimate their spirit or ingenuity. We can make compromises when need be. How else did we pry Mongolia from the Russian grip? And they are helping us with their horse-rearing and yak-herding skills here too. So we will share the glory of winning Mars. There is no shame in this. Better Japan with us than against us, and with the Americans.”

His gaze rose to the stars, in search of a metallic star shining in the night sky above.

***

Kanji was attempting to order his jumbled thoughts. “Mars Terraforming Platform One,” he said out loud to the computer that was obediently jotting down his words. “Atmospheric convertors are pumping oxygen into the air, changing the mix of gases to match Earth composition, but the air is dissipated with the Martian storms. We need water, fresh water, in quantities unimaginable, to dissolve the salt in the sands and purify the soil to make it ready for agriculture to produce oxygen on a scale that oxygen-to-carbon-dioxide mix will become sustainable.”

He stopped momentarily. Everything depended on everything else in an indefatigable circle. Trees and forests were needed as wind traps to break the reign of the storms. But they in turn needed water. Everything depends on water. The planet was saturated with it but the water was saltier than those of the deepest oceans on Earth.

“Desalination would take forever,” he found himself saying out loud. “Life on the planet’s surface is impossible without the hydroponics here. We need greenhouse gases to start warming the planet’s atmosphere with the power of the sun and generate rain that is not salt, alkaline, or acidic. But that, in turn, demands moisture on a planetary scale . . . .”

The sound of his office door opening distracted him. “You need to eat if you are to think clearly.” Yingluo entered, bringing a sugary snack with her from the local mom-and-pop shop.

“Thank you,” he said as heartily as he could. He scooped up the treat with a pair of biodegradable chopsticks. “You know, this would go nicely with some tea.”

“Yes it would.” She left it at that.

He munched away, having become used to these awkward silences. When he was sure he was finished he said, “You are the astrophysicist. I am the lonely botanist and ecologist.”

“First in my class. My thesis was on how to detect gravity waves. I corrected Einstein’s equations. And you were the first in your class too.”

“Do not remind me. Nothing like this has been done before. Growing some spuds inside a shelter on Mars is one thing, changing an entire planet is another. We cannot roof the skies in plastic. There is no measure for comparison.” He sighed, then said, “Where would you go shopping for water, fresh water, in the solar system?”

“Shopping! Because I am a woman?”

“I did not mean in that way. It is just a figure of speech,” he explained apologetically. “But where would you get the water.”

“Earth is out of the question. We do not have enough fresh water there as it is. And the sea levels are declining, everywhere. Two options. Well, three actually.”

“The more options, the better,” he replied.

“First, produce the water locally, from hydrogen and oxygen, taken from anything, rocket fuel, from waste material, from the Martian soil itself if need be.”

“A good idea but too expensive. The electricity needed to fuse oxygen and hydrogen into vapor is too laborious. Separating hydrogen from water for fuel is too expensive on anything but a laboratory scale for us to go and reunite it again to make water. That is why we are still wedded to petroleum after all these ages.”

“I know, may I continue, please?”

“Of course.” He could imagine such a conversation in Communist China. Japanese women had learned from their counterparts habits over the Age of Rapprochement.

“Second, a risky and time-consuming option. Harvest the water from comets. The water on Earth itself is from shooting stars.”

“Fascinating and picturesque. I could imagine our space station docking with an ice harvester on Halley’s comet. But would it not be easier to redirect the comet to crash into Mars.”

“You stole my thought Kanji-sa—Kanji. That is my third option, but with modifications.”

“You are serious.”

“We do not want to wait forever for a comet to approach the Martian orbit. We have the asteroid belt. At the same time we do not want to punch giant holes in the atmosphere or cause gigantic earthqu—Marsquakes or erupt dormant volcanoes.”

“Then it is a question of finding a way to bring the water into the atmosphere, slowly, seeping into the Martian air,” he asked expectantly.

“Precisely,” Yingluo said. “A controlled burn or another method. The rains will do the rest of the work. And we can harvest water from the asteroid ice up here, store it, process it, funnel it down in measured quantities over time.”

“We must coordinate with our colleagues below,” he said with excitement.

“We must coordinate with theircolleagues back on Earth. This is more than moving mountains. It will take a political will greater than it took to win the last war. And we must have all of the calculations ready from now if we are even to convince our superiors, here, that it can be done. May I use your computer?”

“It is not ‘mine’ any more than this station is mine. I simply utilize it. I will go and get myself some tea. There is still the taste of saccharine in my mouth.”

She did not make a comment or an expression. But he could see a smile forming behind the veil of her pitch-black eyes.

***

“But why horses and mules? Are not mechanical vehicles faster?”

They were working tireless on into the Martian night, their bodies still not in synch with the rotation of the planet. The ministry official was sitting behind his desk and his assistant typed away instructions into the computer. His master was obscured by the dark, with only the lower portion of his face illuminated in white by the solar-charged desk lamp.

“The animals are cheaper and easier to fuel and maintain. We have solar power but the panels are still made on Earth from expensive materials we have yet to find here. That is the mistake the American makes. And we harvest the meat and milk and manure and hides of these beasts. One day, one of these days, we will let them loose onto the Martian plateau, where they can graze and reproduce at will, chased by predators we will also bring with us, to keep their numbers in check. We will turn the land into savannah, governed by rainy and dry seasons. Then we also set the savannahs on fire.”

“But why would we do . . .” the assistant realized that he had spoken out of turn, and bowed in apology.

“A brush fire is goodfortune. The saplings cannot reach the light because of the old brush above them, and the carbon replenishes the soil. Death is part of the cycle of life. Black following white into gray, into black and white again. You would think the young longed for this, to replace the old.”

“Never, sir. We all stand on the shoulders of those before us.” He bowed again.

“Do not fret. Our cocooned existence on Earth has made us overlook these facts. Ultimately it is the plants and animals that will inherit the Martian soil, bringing effortlessly with them the balance we so dearly seek and so seldom attain through our technological follies. Then and only then will man follow, beginning with the nomad.”

“The nomad first, sir?”

“Yes. Do you know how the Mongol beat his enemies in our distant past?”

“Respectfully, no sir.”

“You are too young for your job,” he almost snapped at her underling. “By traveling farther in the remotest deserts than anyone else dared to imagine. The Mongol drives two horses, both mares. One to ride to death, one to keep in store for when the first expires, with the rider living first off the milk and blood of the mare and then its flesh when it finally dies.”

“That is terrible, sir,” the younger said..

“It is ‘efficient.’ Nothing goes to waste while the objective is attained. But we are too humane, too soft and corpulent like our own horses to see this. The Apache did much the same. Fortunately for us the American has forgotten his frontier ways and the memory of his efficient enemies. We will use those we have to spread out, faster than anyone else, then we will settle down and turn the planet into an oasis in the night sky and for the horses of the very same nomad. Let us just hope our Japanese allies can figure ‘how’ in due time.”

“But what are we doing here on Mars to begin with, respectfully. Is it profit alone that we seek?”

“We are here to change the face of the future forever. The American reads only his own people’s histories, when he reads history at all. He thinks war is inevitable. America is in decline, like Athens, and so Sparta ‘must’ wage war against it to ascend to the throne. We do not think this way, nor should we. Do you know the story of the great advisor who told a king not to fight the larger enemy plotting and preparing against him?”

“We took it at school, and again in the army. An outsider, a scholar, was given charge of the armies. He forbade them to engage during the first battle. The same with the second battle. The enemy, arrogant with his presumed victories, became negligent and attacked the smaller force for a third time, but by then the larger army had become exhausted, with their supply lines too stretched, and were defeated easily by the smaller force that had become courageous and confident, evading the enemy the past two times.” He fell silent for a moment. “We are here to exhaust the American?”

“In a manner of speaking, if it comes to that. The American has no reason to come here. His land is too big, his life too luxurious. He has no reason to ‘uproot.’ He will only come here in force if he believes he has to, out of jealousy of his rival. And he will spend more money than he needs to convince his people to come. Our population is begging to come. To escape the beehives they live in, the influenzas that kill millions, leaving those alive permanently maimed, the synthetic foods they are forced to gobble down. They will pay usto come here. And what will they do? Who will come? The engineer in search of scrap metal to recycle into engines and bridges. The cultivator in search of clean soil to grow soy and tobacco side by side. The chemist in search of pure substances to process into usable objects. The porcelain maker in search of new ceramic combinations. The corn farmer, in search of land that is his own, not rented from another nation. The man who wants more than one and three quarters children. The woman who is afraid she will lose her husband or boyfriend to the more fertile, foreign neighbor. Women in search of a single husband. ‘These’ persons will build the future, turn the sands green, build our towns, and civilizethe nomad, with time. By then the American will have spent all his father’s savings and polluted his land beyond recognition. The homeland will prosper and will feed our people to become tall and strong like the American. Our industries will thrive and give us the navy and airpower and satellites we need to shelter ourselves behind a mobile great wall stretching from Earth to the skies. With Mars a giant base of operations in the heavens, there will be no room for error and peace will prevail. Now do you see why we ‘have’ to be here?”

“Will we ever see home again, sir?”

“Not in this lifetime. But our bones will be buried with our ancestors. You have made savings for this?”

He nodded, respectfully.

“Again, this is something the American cannot fathom to save for. Least of all the flower of his youth, drowning in a sea of student debt. Wecarry our abode wherever we go with us. The American is too uprooted in his own abode. That is why he cannot win, and he cannot even win over our allies to his side.” His eyes shifted upwards once more, dragging his face out of the limelight of the desk lamp.

The assistant resumed his duties, checking production quotas, as his superior’s machinations were enveloped in the dark.

***

“Your idea, it was not half bad,” she said.

“Which idea was that?” Kanji said.

“Building a giant greenhouse round the planet. That could be done, you know?”

“But how? I was only joking.” He went suddenly silent. “I see! You mean like the rings of Saturn.”

“Yes.” She was overjoyed. “We can have rings of Mars, made of an ice belt. We will use them as wind-traps to capture the lost moisture of the planet that the gravity cannot keep below. Then use them to reflect light back down to heat the atmosphere. The larger asteroids we will crash-land, very carefully, onto the planet’s surface, to create oceans. Oceans of fresh water to purify the sand, on your process which we will name after you.” His eyebrows went up. His firewalls were not as good as he thought. “Then to be populated with plankton and seaweed and coral and fish and crabs and lobsters and—they will breathe life into the air. Other shooting stars we will burn in the atmosphere, very carefully, to avoid holes in the ozone layer we are seeding onto the planet’s skies, which will introduce even more moisture. I have the calculations all ready, thanks to the cooperation of ‘your’ computer.”

He patted the machine with pride, clad in white plastic with a dark screen and black metallic keys. “Your first name is Yingluo?”

“Yes, a Chinese name in origin. My mother gave it to me. She learned it while taking Chinese cooking lessons.”

“It means jade, am I correct to assume?”

“Precisely. An allusion to a string of jades in a necklace, like truths following each other in an argument of pure reason. And Li is a reference to reason, and ‘to set in order,’ with roots in Chinese.”

“You have been doing your homework,” Kanji said, unsurprised.

He paused himself before adding, “Mikao is Japanese for new moon, is it not?”

“My father wanted me to be an astronomer, like him. He always felt his name had destined him to that fate. So my mother found a scientific name to her satisfaction. And your name is similar to the Greek cosmos.”

“But it not as poetic as the Chinese,” he replied. “And I have found myself working beneath the stars, like my own father. Do you know what my grandfather said every Japanese man’s dream is?”

She pursed her lips, exposing two perfectly spaced dimples in the creamy white of her skin. She was weighing his response.

“To live in an American house, marry a Japanese woman, and eat Chinese food.”

“Do you know what mydream is?”

He did not venture a guess.

“To marry a cosmonaut who lives on the ground!”

***

“Look, look!” The ministerial representative pointed to the black expanse of night sky, from his seated position in the wheelchair.

His assistant, now sporting gray temples, watched as the first balls of ice began to turn to fire. “Blue to red to blue. How can this be possible, sir?”

“Our allies have realized who is more useful to them in the future.”

“The data they downloaded to us, it says they will also position balls of ice around the planet.”

“Like pearls in a necklace, beautifying the neck of a desert bride.”

“And warming the desert with moisture till it is a desert no more,” his assistant continued, less poetically. He was now wearing an Uighur coat over his green-gray uniform. It kept him warm in the cold Martian night.

The ministerial representative coughed. His lungs had ingested too many homegrown cigarettes over the years. The stress of the job was finally getting to him. “First order of business, once the fireworks are over. We have guests to chaperone round the planet. The company employing them, the company responsible for the space stations, wants to build Japan-towns on the old Chinese model, in our underground cities!” He almost laughed out loud.

“It will never work. They will be absorbed by us, sir. Even the Uighur has come around to our ways.”

“The Japanese knows how to divide his mind between what is domestic and what is foreign, but as long as it helps him be creative in our aid, who are we to complain? You must give others some space to thrive. A horse cannot grow to fruition in a cage.” He read through the tourist manifest. “Oh my goodness.”

“What is it, ministerial representative?”

“I wish to house this middle-aged couple in my ownhome. Imagine that from me, and I cannot abide the smell of rice wine. Still, they are to be honored guests wherever they go. Is that understood?” He said sternly, with a fatherly look on his face.

“Of course. Will they be coming alone, sir?”

“No. They have children. Their eldest girl is almost the age of my grandson. What a fortunate cosmic coincidence!”

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Simon, Marcia and Chisei.

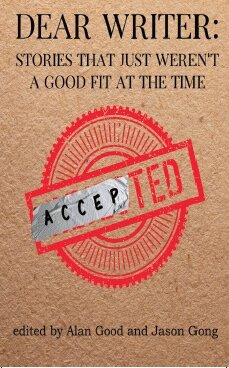

Always available on Bookshop, Indiebound, and Amazon.

Dear Writer: Stories That Just Weren’t a Good Fit at the Time collects ten stories that were each rejected at least ten times. Several were rejected many more than ten times, but they’re all very good stories. Edited by Alan Good and Jason Gong, Dear Writer features work from Sarah Evans, Yousef Allouzi, Karen Thrower, Jennifer Porter, Anna O’Brien, Sarah Yasin, Emad El-Din Aysha, Lituo Huang, Rosaleen Bertolino, and Ellen Ricks.