"Breakfast With Dad" by Paul Lewellan

Originally published in Moon Reader (May 2001)

It’s 5 a.m. I’ve been awake for an hour. I know my father is downstairs drinking coffee. Beside me Beth softly snores. Last night we argued in whispers until after midnight. She blames me for Dad’s presence. She says he disturbs the aura of the house. I get up, knowing what I have to do before she wakes.

I approach the kitchen quietly, trying to catch an unobserved look. The sun coming through the east window provides the only light. He sits on a chair from Grandpa Bauer’s farm. Spread out on the quarter sawn oak table is the cartoon section of the Des Moines Register. That means he hasn’t been there long. He always reads Peanuts and then turns to Family Circus. Sometimes he laughs, “Where does he get these ideas?” Occasionally Dad reads Blonde or Beetle Bailey, but today he closes the comics quickly and turns to the front page.

After scanning the headlines, he acknowledges my presence with a nod and begins reading on trade talks with China. He stops sporadically to take a drag from his Lucky Strike and sip the steaming black coffee. His wispy gray hair is neatly combed across his nearly bald head. He wears a dark blue plaid short-sleeved shirt and a pair of tan pants with worn pockets. His shoes are a well-polished old pair of brown Florsheims. Only the shimmer of air around his head and hands hints that he’s been dead for almost a decade.

I go into the kitchen and turn on the light. “Thanks,” he says. “It was a little dark,” He adjusts his wire-rimmed glasses around his ears and returns to the paper. “I made coffee.”

My body tingles in anticipation of the caffeine. My father measures a heaping spoonful of coffee for each cup of water, plus one for the pot. I pour myself a cup and sit down across from him.

Beth only serves decaffeinated coffee, but the day Dad arrived three weeks ago, a three-pound can of Folgers regular grind appeared in the refrigerator. Beth threw the can out that afternoon while Dad napped on the green couch. “I don’t want that stuff in my house,” she told me. But the next morning Dad reappeared at the breakfast table and another can of Folgers occupied the top refrigerator shelf.

Dad reads the Des Moines Register daily, though Beth and I haven’t subscribed for five years. I don’t ask how it gets there; I just grab a section and dig in. I don’t make conversation. He rarely speaks. I sip from my Roy Rogers mug with the gold rim that appeared with Dad. That mug from my childhood was a fixture in my school office until a decade ago when the night custodian broke it while vacuuming.

I look at the Register’s front page, now a wall between us. There is a small greasy stain in the center where he’s rested the paper on top of a half-eaten slice of buttered toast. He takes another drag from his Lucky Strike. I know if I turn around, I’ll see a newly opened loaf of Wonder Bread by the toaster. “Helps build strong bodies eight ways,” the package says. Fifty years ago Wonder Bread changed its slogan to “builds strong bodies twelve ways,” but Dad never approved of the last four ways. He’s been resistant to change ever since his death.

Beth is intolerant of Wonder Bread in any form. We eat gluten free bread that she buys downtown at the Gemini Bakery.

I take another drink of coffee, and then plunge into the conversation. “Dad,” I say, “I’ve been wondering why you came to visit,” I think it’s best not to mention his demise. I assume he knows about it. I don’t bring up the magic tricks either. I curious, but they aren’t the issue.

A slight rustle of the newspaper acknowledges my statement. I wait. That’s what a person does with Dad. When I was twelve, I used to lean against the oak and glass walk-in cooler in the corner grocery store my parents ran. I’d watch him wait on small children at the candy counter while my questions hung in the air between us.

Dad puts the newspaper down on his toast again. Apparently, he expected the question and has a response ready. “Have I overstayed my welcome?”

The answer surprises me. It’s one of Mother’s questions. She asks it thirty seconds after she arrives and continues asking it until the day her packed bag appears at the bottom of the stairs. That’s when she announces, “Can’t keep the store closed too long. The neighborhood will wonder what’s happened.”

At home in Cedar Falls, Mother is waking right about now. She’ll scramble two eggs and listen to the morning news on the turquoise radio she got for starting a new savings account at First Bank and Trust in 1963. Just before the hog market reports, she’ll take her dishes to the sink, and then walk the few steps through a small entry way into the back of the attached grocery store. In the eight years since Dad died, she’s been making that walk alone. Before then, they’d walked it together, six days a week, fifty-one weeks a year, for forty-two years.

I look over to Dad. He waits patiently for my answer. “No, you haven’t overstayed your welcome. I enjoy the company. I haven’t had a decent cup of coffee since we gave up caffeine,” He smiles.

Dad goes for the newspaper again. I shift in my seat. That’s Morgan family body language for “I’m not done talking yet,” He puts the paper back down on the toast.

“I think, Dad, that you came for a reason.”

He crushes his Lucky Strike in the Thunder Bay ashtray he brought with him, the one with the large painted walleye. He reaches for another cigarette. “Your mother’s upset.”

I’m not sure how to respond. “She didn’t mention it the last time we talked.”

“You don’t know her like I do,” he tells me quietly.

That’s true enough. To me she’s Mother Courage on steroids. To him, she’s his life’s love, companion, and business partner. She’s his rival at cribbage, and the only woman who can pickle a calf’s heart to his tastes. “Why do you think she’s upset?”

Dad takes off his glasses and sets them beside his coffee cup. He rubs his one good eye as though he’s tired from reading. I know he’s stalling. “She threw away my electric shaver. I went into the bathroom, and it was gone. And so was the Old Spice, my Polydent, and the box of little pads I used to put on my feet for corns,” I stare at him blankly. At Easter all those items were still there, despite his death eight years ago.

I reach for my coffee cup, but I’ve already drained it. I clear my throat. “Dad, you don’t need the stuff.”

“You don’t understand,” Suddenly the newspaper is up blocking his face. I know he isn’t reading because he hasn’t put his glasses back on.

“She’s got your picture in every room. The house is a shrine. She’s kept every article of clothing you ever owned.”

“No, she was boxing the clothes for Goodwill when I left.”

“Oh.”

He puts the newspaper down. “She kept everything the same after I went to the nursing home because she knew I was coming back. If she’s packing things, she’s stopped waiting for my return.”

“But Dad,” I say awkwardly, “you’re dead.”

“Oh, I know that.”

I fill my Roy Rogers cup, then pour him a refill, too. “More toast?” He shakes his head. I put in a couple slices for myself. “Mom goes on cleaning binges. Remember when you and I were fishing in Canada? She emptied out my comic book collection, a year of Esquire, the Girls of the Big Ten Playboyissue, and all the National Geographic.”

“That was different,” he tells me.

“Do you know how she’s been doing since you came to visit me?”

“I’m told she’s been lonely.”

“I wonder who’s making the coffee.”

“Oh, that’s always been her job. She never lets me touch the pot. That’s why I like visiting you.”

“What if she’s started drinking Sanka again?” I watch him consider this prospect. When he was diagnosed with ulcers, Mother bought a 32-ounce jar of instant Sanka and hid the Folgers in the linen closet. The Sanka lasted twenty-six hours before he flushed it down the toilet. My father drank Mylanta with his coffee but refused to surrender his caffeine again.

“What if she starts dating again?” he asks me.

“Dad, you’re the only man she’s ever loved. Just because she doesn’t want your old deodorant around, doesn’t mean she’s ready for the singles bars.”

Dad stands. “Maybe not,” He picks up his Luckies and puts them in his shirt pocket. “Should I stay until Beth wakes up so I can say good-bye?”

“I don’t think that’s necessary. I’ll give her your regrets.”

“I could make another pot.” He motioned to the turquoise percolator that replaced our Mister Coffee when he arrived.

“Dad, your coffee makes Beth nervous.”

He shrugs.

“I’d appreciate it if you’d leave the paper and the coffee mug.”

“No problem,” He pats Grandpa Bauer’s chair. “I did some shopping. The stuff’s in the frig.”

I nod. We were never much for hugs. I watch him leave through the back door. After a moment of mourning I go to the refrigerator. On the top shelf are a fresh can of coffee, a 16-ounce jar of pickled pigs’ feet, and a small wooden tub of herring in wine sauce.

I hear Beth stirring in the bedroom, so I hide Dad’s gifts in the crisper drawer until she leaves for work. I sit down to finish the newspaper. I hope there are saltines in the cupboard, but I’m sure Dad wouldn’t forget something that important.

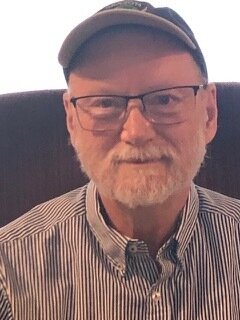

For almost five decades, Paul Lewellan taught in the public schools and private colleges. Now he lives on the banks of the Mississippi River and with his wife Pamela, a certified fraud examiner with literary sensibilities. They share their cottage with an annoying little Shi Tzu named Mannie and the queen of the house, their ginger tabby Sunny. They are currently sheltering in place, which for a writer, is like any other day. Paul’s short stories have appeared in Front Porch Review, Big Muddy Magazine, Porcupine, South Dakota Review, and over 120 other publications. For more of his fiction, google his name and sit back. Email: plewellan@mac.com Twitter: @Paul_Lewellan